In the West, we are told consumers are value seekers. Confined to the notions of Angelo American capitalism, Westerners seek to maximize utility per unit dollar. In the West, they frown at the idea of a system that isn’t a meritocracy, but in China, relationship bias is embedded into culture. From the very first day of China, Laowai are taught the important of Guan Xiculture. Westerns — perhaps more specifically Americans — are comfortable with the idea of sacrificing human relationship with vendors for the convenience of delivery. Technology has driven us closer and closer to products and further and further from those that create these goods. Adam Smith would be so proud. Blinded by our sense of value, we lose our connection to labor — or so we thought.

In China, cash is still king, but relationships are the rule of law. As China has developed, they largely maintained their relationships with merchants. Perhaps this is the difference between a people’s republic and a capitalist democracy, or perhaps this is just the idea of Chinese characteristics.

It’s silly to think in these extremes, however. China isn’t entirely a Guan Xi culture, and the West isn’t completely capitalist society. It’s a spectrum. After all, perhaps no country in the world values tipping as much as Americans — an act that is inherently related to the interaction between labor and customer. And who’s to say Zhongguo Renaren’t value seekers? Perhaps they’ll stay loyal to a vendor that they believe gives them a fair value, but who’s to say they won’t switch vendors if that value disappears. And who’s to say Adam Smith didn’t have a little Guan Xi.

To understand where Western and Eastern consumers lie on this scale we decided to survey some of our friends to understand the relationship between consumers, vendors, food, and convenience.

NYU Shanghai’s “Street Food Ladies”

No. 166 Yushan Road, 500 meters away from the Academic Building, stands NYU Shanghai’s previous dorm. Usually being called “268”, it used to be a Motel 268 and then served as the temporary student dorm. Walking down Yushan Road after around 9 pm, a powerful aroma of fried rice and lamb fill the air as street food patrons gather with smokes blowing up to the sky. Whenever NYU Shanghai students talk about their college experience, chuanr and chaofan almost ubiquitously elicit nostalgic responses.

As nearly any student can tell you, the street food vendors and their cooking have filled an essential aspect of college life. Long-night struggles and after-party conversations typical NYU Shanghai students’ implicitly revolve around street-food. “Grabbing some Chuanr” has become a normal way of socializing in the community.

Vendors have been dubbed “Street Food Ladies” by students. Street Food Ladies typically stood beside their husbands, adjacent to the 268 selling stir-fried rice noodles. Unlike other street food spots, Street Food Ladies developed a special relationship with the whole student body — everyone knows them, almost every student has experienced their food before, and their customers are mainly NYU students. After the move-out of the whole NYU dormitory, the “Chuanr Lady” decided to follow her loyal customers to the new JinQiao dorm. However, students had to say goodbye to rest of the other vendors along Yushan Road. This historic move-out has impacted the student community. Some student have gone without street food, while others visit their old friends on Yushan Lu quite often. The dynamic and inseparable relation between NYU Shanghai students and street food vendors is indeed complex. We thought this a classic example of “Guanxi” society and a Chinese cultural context.

We invited four Shanghai students, two Chinese and two internationals, and had interviews with them individually. We were trying to explore if there are any differences between New York students and Shanghai students’ attitude towards street vending around the community and how they consider their relationships with the vendors — Street Food Ladies especially.

The interviews were extremely interesting and surprising. It ended up having a completely different result from what we expected before. We structured the questions mainly focusing on students’ need, preference of food, their frequency of going for street food and their perspectives on the student-vendor relationship.

We were trying to understand why students at NYU Shanghai continue to frequent the “street food ladies”.

The questions are attached here.

We were very surprised to learn that they claim that they go for street food for convenience, instead of a relationship. When asked, “would you be sad if the vendors would close down tomorrow?” and “would you still choose to go for the vendors even they moved away?” all four students answered that they would rather choose vendors closer than going back to their old Lao Ban. As Bill pointed out:

“The food is just a necessity. There is probably a connection beyond food between students and vendors, but in the end the relationship is more likely an approach to convenience and price.”

It seems as though a capitalist mentality is not unique to the West, as price and convenience have more of a universal appeal.

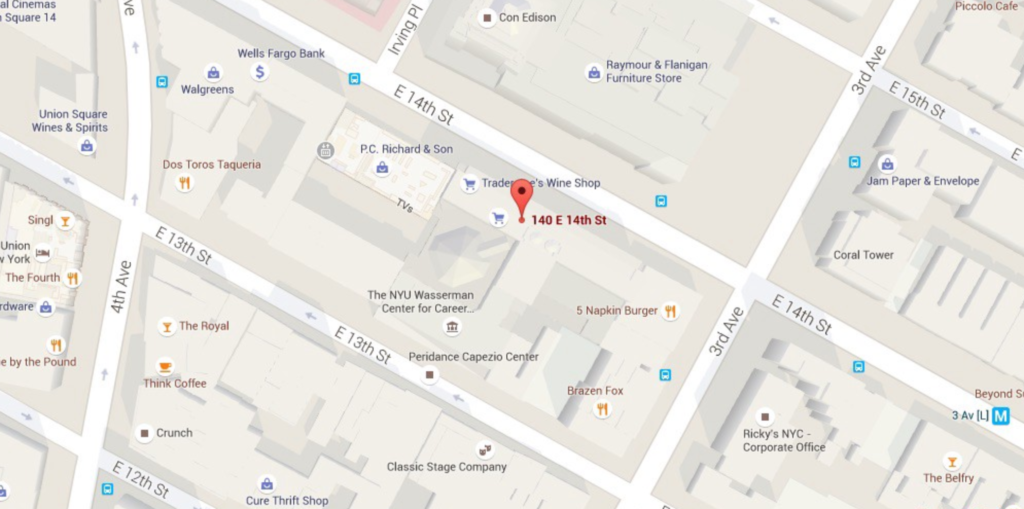

Farook’s Halal

On14th Street flanked by 3rd and 4th Avenue is what is known locally as Halal Alley. Five separate halal carts operate for nearly 20 hours a day. For those that enjoy a late night meal, the smell of Halal Alley is almost beckoning. At nearly any hour of day, lines of mostly twenty-somethings wait to exchange their five-dollar bills for a taste of the Middle East at a highly reasonable price. The vendors that quite literally slave over the the food are almost ubiquitously referred to as “halal guys.” The relationships that develop between merchant and customer rarely get past “hello, may I take your order?” After all they are just merchants in the sea of commerce that is New York City.

Yet despite the capitalistic mindset that seems to dominate all transactions on Halal Alley, there is one vendor that it is always referred to by name. As one of the customers — Alec Pan — said, “When I think about halal carts, it’s halal carts and then Farook.”

“It’s a delight to the senses.”

Farook’s Halal is located on the South side of Halal Alley. His stand sits between two other vendors, who serve the exact same thing for exactly the same price. In perhaps one of the most distinct deviations from Michael Porter’s Competitive Strategy, these vendors have seemly done nothing to give themselves a competitive advantage. Except Farook. “Once you try Farook’s, you can never go back,” Daniel Kim, another regular customer, proclaimed. Dan says he typically visits Farook “around 4 times a week,” and while his patronage may veer onto the extreme, his loyalty isn’t atypical. Krishna Sridharan, another student we talked to said, “If Farook wasn’t at the helm, I wouldn’t get food. I’d just walk away.”

Of the four customers we spoke too, only one customer — Charles Zhao — said he ever eats anywhere other than Farook’s. He added that he wasn’t a “regular customer” of anyone else’s cart. Almost all of Farook’s customers share an almost religious devotion to Farook and his food, but what causes this allegiance isn’t abundantly clear. We set out to determine what exactly keeps consumers coming back to the only named halal guy.

When you talk to people about Farook’s halal, one of the words you’ll hear is value.

“Farook’s is the best value in New York… for anything.”

It’s interesting to note that all the customers felt they were getting value even though they all had different standard orders. Dan orders chicken over Rrice. Charles prefers a combination of lamb and chicken on top atop his feast. Krishna, a vegetarian, opts for a gyro. Alec a convert from chicken over rice, has switched to lamb and likes barbecue and “white sauce” on his late night snacks. We thought these customers in particular would have a good sense of value because they are all business students, but as Charles put it, “any 12-year-old can tell you that $5 for that much food is a good value.” Dan, who has perhaps the most extreme view on Farook’s cooking, said he would pay over $100 dollars for a typical chicken over rice. Although this ascertain seemed extreme, he explained his personal relationship with food and compared it to other meals he’s eaten at Michelin Star Restaurants. He considers Farook’s chicken over rice to be in his top five meals he’s ever had, which he determined would justify paying into the triple digits for a Styrofoam encased meal.

Everyone we interviewed took a trip to Halal Alley to visit Farook at least once a week. Not only are they loyal, but they are also regular. It’s seems natural that if you see someone that much, you would naturally develop a relationship, and to a certain extend they did. Charles mentioned that with his patronage comes perks. He noted that if he didn’t have enough cash on him, Farook would allow him pay the next time he came. In doing so, by operating “The Bank of Farook,” he encourages Charles to come back to his stand to pay him back, and hopefully order another meal. Although Charles was the only one who talked about meal financing, everyone insisted that they had a relationship with the vendor.

Charles, Krishna, and Dan all have Farook’s phone number. This, we originally assumed, is how Farook differentiated himself. We thought just like a stereotypical American, they just craved the convenience. Charles, who after initially insisting that he thoroughly enjoyed his conversations with Farook’s, later capitulated that he’d rather forgo exchanging pleasantries with Farook in exchange for the the convenience of being able to call ahead the pick it up. Moreover, Charles admitted that even if his service was below par, he would still frequent Farook because he’s simply the most convenient. Although Charles insists that “he really does appreciate” how nice of a guy Farook is, he truly embodies what we originally thought of a Western capitalistic consumers.

Dan and Krishna were adamant that it was not the convenience, but rather the actual food. As Dan succinctly explained, “It’s all about the product.” Krishna claimed he would willingly walk several blocks and wait twenty minutes to get his midnight snack. Dan, true to form, said he would wait “over an hour on the coldest day of winter” to get his chicken over rice. He also points out that other customers who are former residents of Halal Alley, will come from relatively distant neighborhoods like Midtown and FiDi to visit Farook. It’s truly a pilgrimage.

Dan and Krishna’s devotion to Farook is also unwavering. Unlike Charles, who would occasionally flirt with other vendors, Dan and Krishna were resolute in their commitment. Never at a loss for words when talking about Farook, as Dan put it:

“As a smart, rational-thinking economic agent, once I figure out the best seller on the market, I don’t go to any other seller.”

Unlike Charles who admits that he really “has a relationship with convenience,” Dan and Krishna — particularly Dan — have a relationship with the physical product. Not unlike Charles, however, they too are maximizing their utility per dollar; they just derive their utility in different ways.

The way Alec talks about Farook and his halal isn’t nearly as romantic as the way Dan, Krishna, or even Charles would describe it. He too, however, is a loyal disciple. Alec actually prefers the food from Halal Guys Restaurant, located just 2 avenues away from Farook’s cart. Unlike going to any of the carts on Halal Alley where all the prices are all the same, you pay a premium when you go to the restaurant. Alec says the combination of the price and distance is what keeps him from going to Halal Guys Restaurant more frequently. In direct contrast to everyone else we interviewed, Alec cannot differentiate Farook’s product from any of the other vendors. So why is he so loyal?

“I default to Farook’s because he is what I believe to be, a nice guy.”

Service and relationships very much matter to Alec. “Part of the reason I come back is Farook’s personality.” He spoke at length about how Farook and how courteous he always is, even when he deals with customers that are rude and a bit rowdy. As Krishna put it, “That’s why we know him as Farook and not just another Halal guy.” Of all the people we spoke with had nothing about positive things to say about the man himself.

We asked all four consumers what they knew about Farook other than his food. The results were remarkably unimpressive. We used an NYU Local Article as a reference. Dan was the only one that was able to approximate how long he had been making Halal (13 years). Only Charles was able to identify Farook as a parent. He said he knew Farook had “a son or daughter,” but in fact he has both a son and a daughter. Incredibly, no one was able to correctly identify where Farook was from (Bangladesh). This lack of background information is important to understanding the dynamic between Farook and his customers. As Dan put it, “it all starts from a business relationship.” Their lack of basic knowledge indicates their relationship has hardly advanced despite their patronage.

If we proved anything, it’s that a one size fits all model of Western consumers simply isn’t accurate. Consumers are driven by price, product, and personality in some combination thereof. It does, however, seem that Western consumers care more about convenience and price than about the actual relationships.

Conclusions

Wecame into this project with an almost dubious view of Westerners, but we emerged with a more complicated view of capitalism and relationships.

We originally thought that Westerns would be driven more so my economics than relationships, and when we spoke with Michael’s American friends this sentiment was largely reflected. We observed that NYU Shanghai students were also guided by Smith-like “invisible hand.” The ideals of capitalism — the value of convenience and price — are not uniquely Western.

This discussion also brought up deeper questions about identity and culture. When Michael was selecting his friends to interview for this project, he unconsciously selected four first-generation Americans. Do they really epitomise “American” or “Western” consumer values? When Ben interviewed NYU Shanghai students, two of them were not ethnically Chinese and only spent a few years collectively living in China. Are they truly Chinese consumers? Perhaps even the the Chinese nationals were subject to bias. Does attending an American University skew your perspective?

Alec, who is Chinese-American and is currently studying abroad in Shanghai, put forward a new model for understand the dynamics between merchant and customer that we call Guan Xi Capitalism. In situations where merchants cannot differentiate their products or services, they can use relationships to give themselves a competitive advantage. Although Alec saw no difference in the products of Halal Alley, his relationship with the vendor drove his continued patronage. In Shanghai where the vendors are fewer in the late night hours, he largely has not formed the same type of relationships with street vendors. He attributes this to their late night monopoly.

After living in both New York and Shanghai, Alec pointed out that relationships have an important role in both cultures. Alec said he if street food vendors had taken the time to develop a relationship with him, he would be more willing to venture outdoors when the weather is cold or raining to buy street food. What this suggests is that relationship cannot only help vendors gain a competitive advantage, but also shift their demand curve outward. This means we can’t think of relationships and capitalism separately — they are inherently found in each other.

Alec’s ability to straddle the East and the West and the concept of Guan Xi Capitalism can help us to understand an ever-changing global economy.

Man. I’m hungry. Chi fan hao ma?

Learn More

Full interviews with Krishna, Alec, Charles, and of course Dan.

Article about NYC Halal featuring Farook.

On Century Avenue Article about Chuan Lady

Directions to Farook’s Halal Cart. Remember he’s the one in the middle!

Directions to Chuanr Lady.